Obstacles to Voting:

Most soldiers used state absentee ballots NOT federal war ballot.

Unlike today, voting for the World War Two serviceman was not such a straight forwarded affair. Numerous obstacles were in place to make absentee voting difficult or non-existent. It took a series of changes, each building incrementally to loosen-up the restrictions in time for the armed forces to vote in the Presidential election of 1944. One of the biggest changes was the political shift of the Republicans to allow (or at least not inhibit the democrats) a federal presence in what is to be considered an area of state’s rights.

In 1940 voting was extremely difficult. The military only allowed one day of leave for voting. With individuals being drafted it was almost impossible for a service member to have the travel time to go home, vote, and come back.

Civilian absentee voting was practically non-existent. In the few states that had absentee voting some outlawed it for the military personnel. Even if a service-member could vote, absentee restrictions were placed on the type of election. For example, SC allowed military members to vote absentee only in democratic primaries and in New Hampshire only for presidential electors (Carter 22).

Assuming an individual met all the requirements and the state allowed voting for military members they ran into issues with mailing. Soldiers would have to pay postage to request voter registration forms. Pay postage to return those registration forms. When the ballots came they came in “heavy envelopes.” (Carter 23) A soldier had to pay the return postage on those too. Some states even required registered mail which drove the cost up even more (Carter 23).

Finally, service-members were required to submit to literacy tests, grandfather clauses, poll-taxes and be 21 to vote. Literacy tests and poll-taxes in some states were required to be taken or paid in person.

Even if a soldier made it through all the restrictions, in some states, the mere matter of being in the military meant that the solider was no longer a resident of that state and therefore did not qualify to vote.

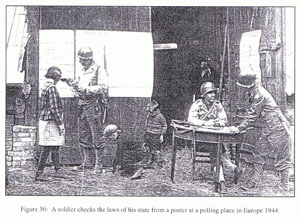

Despite the problems with voting, the states wanted the military to post their rules and regulations. The military balked at the request as it do not want to post up to 48 different rules and regulations at each fort, base, and camp. The states petition Congress to find a solution in time for the 1940 Nov. election. Though Congress did not reach a practical solution, a compromise was found. The military allowed states (who footed the travel bill) to send in officials to conduct “on-the-spot” voting at various camps (Carter 23). Arkansas, Iowa, KS, and NY took advantage of the compromise and sent officials out. Those at camps without “on-the-spot” voting were forced to mail their vote in.

1941

The voting system changed little between 1940 and 1941. If an individual desired to vote in local, state, special, or primary elections he or she would be required to submit the cumbersome absentee-voting process. No on-the-spot voting was done in 1941. Though, one notable adjustment was NJ, OH, and PA allowed for individual military absentee voting.

1942

Things begin to change in '42. AK, Iowa, KS, and NY did send out officials for on-the-spot voting and 45 of the then 48 states had some form of military absentee voting in place (Martin 725). Congress recognized the need and made a first attempt at sorting out the issue of voting. The Ramsey Act (Public Law 712) was passed and went into effect on Sept. 16th, 1942, six weeks before the election Nov. Congressional election (Carter 24). The act allowed for the free regular mailing (not airmail) of election materials. If a soldier wanted to airmail his ballot he would have to pay the additional costs. Also, the poll-tax for the upcoming federal election would be paid by the federal government though state literacy tests and other voting requirements still remained.

The act also allowed a service member to vote under the state absentee ballot process or use the federal application form to request a state absentee ballot. States that did not have absentee forms by default had to use the federal application form. In the end, the lateness of passing such a law meant that “not much could be done other than post information.” (Anderson 86).

While both the Army and Navy had forms for applying to receive state war ballots they did not have legal standing in the states. Many BNP-105 (the Navy’s form) and Form 460 (The Army’s form) were rejected by the states. Despite this, some localities passed local ordinances allowing military members to vote absentee in that locality. Somerville, MA allowed for such a condition for its 1941 local elections (Carter 24). In the end, out of the then five million servicemen, 137,000 service members used the forms to obtain state voting ballots. Only, 28,000 of the state war ballots mailed out were returned (Carter 25). New Jersey had the most mailed out at 58,097 and Vermont the least with 128 (Carter 27). Out of the 29 million who voted in 1942 the effect was minute (Anderson 90). While turnout was low it was the first attempt by Congress to provide standardization in the voter application process.

1943

The system of voting for state, local, special and primary elections was essentially the same in that in 1942. Basically, a soldier would write home to their states Secretary of State for voter registration materials. One would complete the registration form and mail it back. A soldier would receive the ballot, complete it, and mail it back. While variations of this process existed dependent upon state laws, at least the soldier could now send and receive voting materials through the mail for free. Though, because this was an “off-cycle” election, the federal government did not pay poll-taxes. Soldiers still had to meet the requirements of their individual states to vote. With the 1944 presidential election around the corner, Congress began examining the issue closer.

1944

Example of the state ballot in the 1944 primaries:

In 1944, with 11 million individuals serving at locations across the globe there was a need to provide some sort of standardized procedure and forms as the military could not provide 48 different ballots and list each states rules and regulations at each military installation around the world. Several bills were proposed in Congress attempting to provide standardization in voting. The primary issue seemed to be state’s rights vs. a military service-member’s right to vote. While the Southern Democrats cried “states rights” the Northern Republicans were worried that the military-vote might go to Roosevelt. Soldier’s overseas also took notice of the events surrounding a Soldier’s Voting Bill. In the March 17th, 1944 edition of YANK many soldiers writing from across the globe including, Australia, Britain, the Aleutians, Iran, and South Carolina argue fervently that state voting laws are to ridged and that delaying the bill and the lack of a federal absentee ballot are tantamount to a denial of the right to vote.

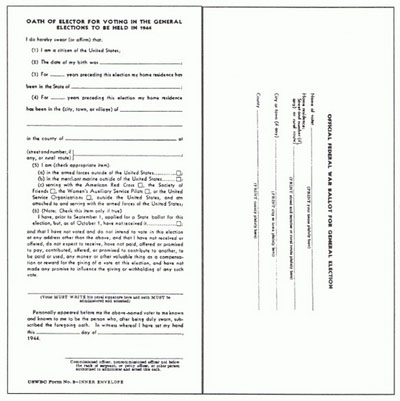

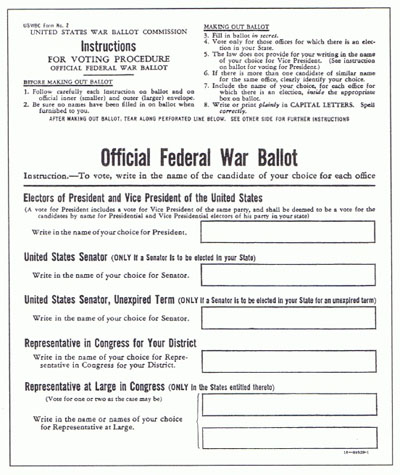

A compromise was eventually reached in Congress whereas the overseas military voter would attempt to register to vote using state procedures. If the registration materials did not reach the individual by a certain date, s/he could then use the Federal War Ballot only if the state had approved the procedure. The federal government would now be creating an actual ballot for soldiers to use. Though it would only list the federal officers. Soldiers could vote on the new ballot by, “…specifying either the names or the political party of the candidates of his choice” (Martin 727).

Roosevelt telegraphed all 48 governors asking them their intention on the use of the Federal War Ballot. Support was lukewarm with half the states having legislation already in place that approved the federal ballot or were working on it. The states that supported the use of a Federal War Ballot were: CA, CT, FL, GA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NC, OK, OR, RI, TX, UT, VT, WA (Carter 51). KY and NM used the federal ballot by default as they had no absentee voting laws in place. The rest did not respond or were noncommittal. With hesitation, Roosevelt allowed the bill to become law without his signature on April 1st, 1944.

The process for voting in the 1944 election was as follows (Carter 31):

1. Apply for a state absentee ballot using either the state requirements in applying (ie sending a letter to the secretary of state or the local election official) or use the old War Department Postcard/Form 560 from the 1942 election. Individuals could also submit their own application using specific guidelines. In at least one instance, an entire army created their own application. The US 8th Army actually printed their own federal absentee registration forms (Carter 61).

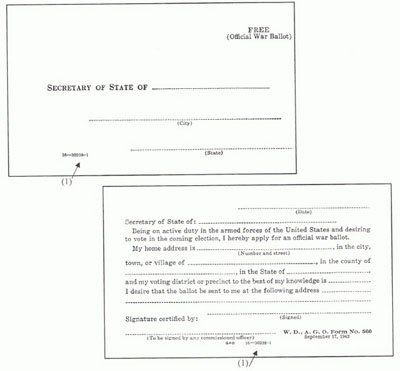

War Department Form 560- Federal Application for State Ballot

Example 1:

Example 2:

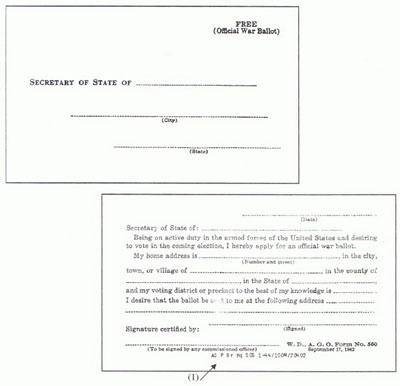

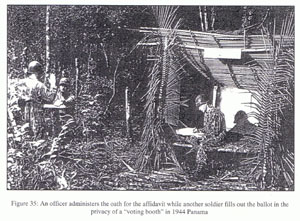

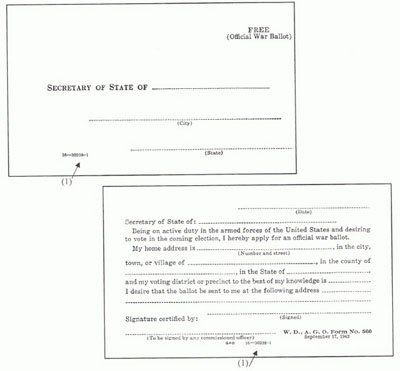

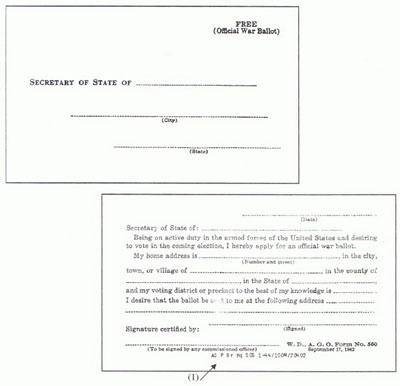

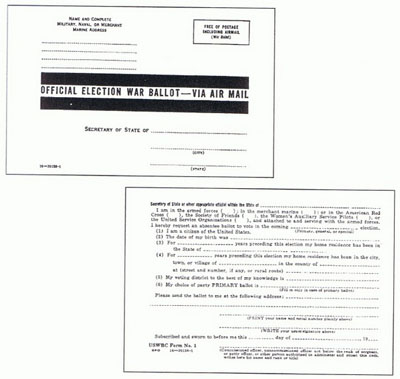

Additionally, to register soldiers may also use a form created by the USWBC (US War Ballots Commission): Forms 1,3,4 (Form 2 is the actual Federal War Ballot). All types were created for the 1944 election. In using the Federal War Ballot it required an officer as witness.

USWBC- Form 1, Federal Application for State Ballot

Example 1, Form 1:

Example 2, Form 3:

(Note: In the Form 3 example, it shows what USWBC registration form, contained inside all applications looked like)

Example 3, Form 4:

The state ballot an individual would receive would consist of the local, state, and federal officials. The return state ballot must be submitted within the state war ballot return envelope.

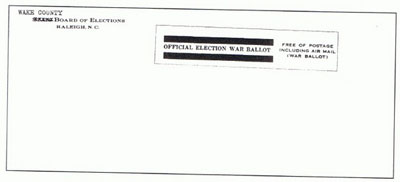

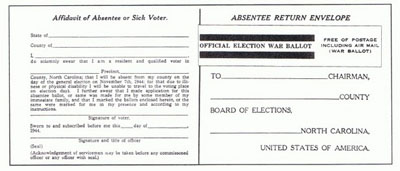

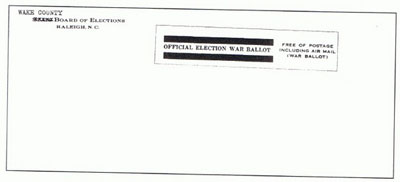

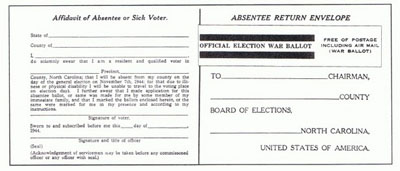

North Carolina Return Envelope for State Ballot

Example 1:

Example 2:

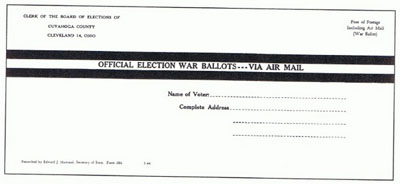

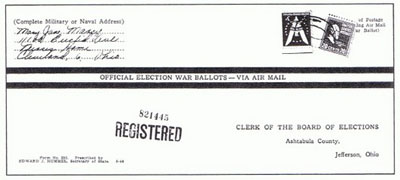

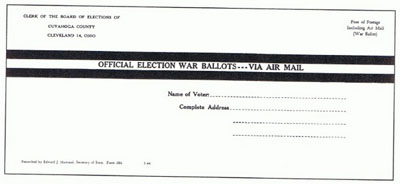

Ohio Return Envelope for State Ballot

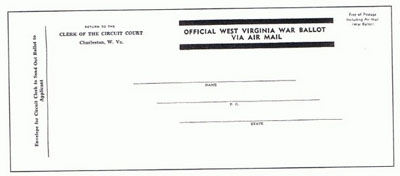

West Virginia Return Envelope for State Ballot

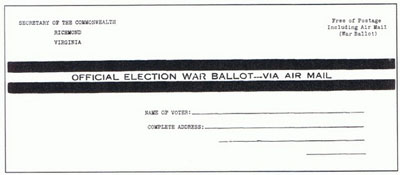

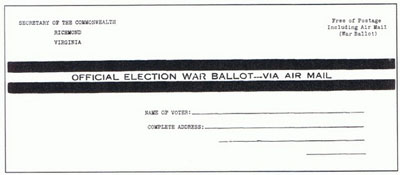

Virginia Return Envelope for State Ballot

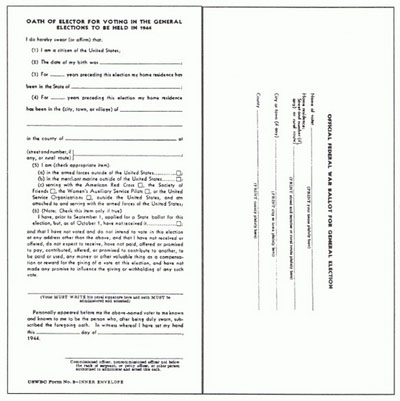

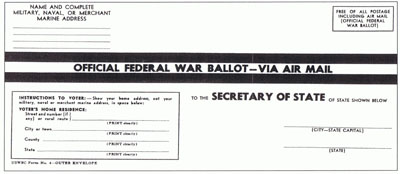

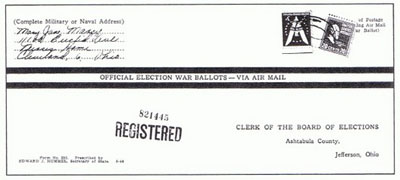

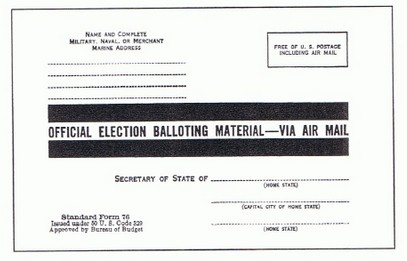

2. If by Oct. 1st, 1944 the person had not gotten the state ballot and had mailed/requested one before Sept. 1st, 1944 you would be eligible to use the Federal War Ballot. This ballot only listed the federal officials running and could only be used in the state that had approved it. The ballot had to be submitted within the federal war ballot return-envelope.

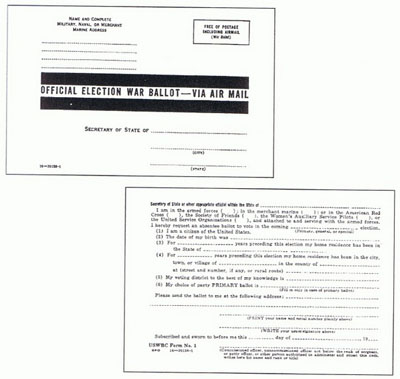

USWBC- Federal War Ballot

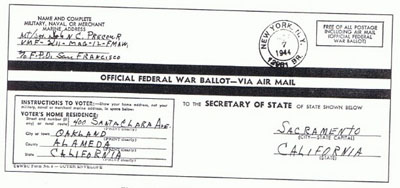

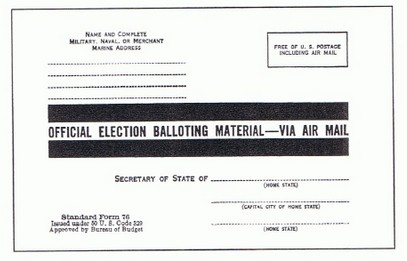

USWBC- Federal Return Envelope to mail Federal War Ballot

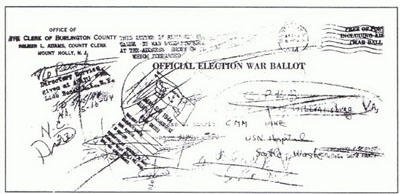

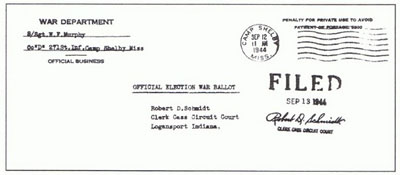

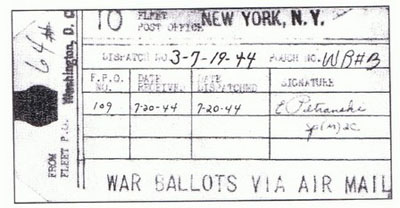

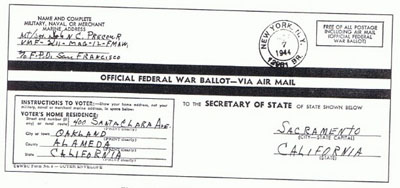

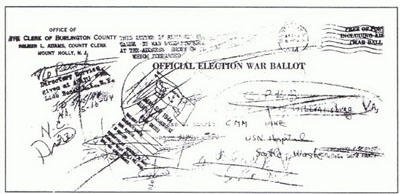

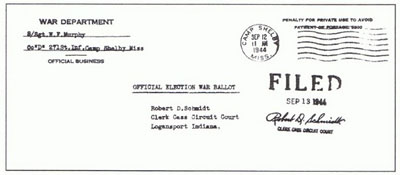

Example of a Returned Federal War Ballot Envelope

3. Vote according to state procedures

Example of having registered mail to vote:

4. If a conflict arose between an individual submitting both a state and a federal ballot, the federal ballot would be thrown out.

Example of Overseas Military Voter Fraud

The War Department distributed the Federal War Ballots to authorized personnel to the Army, personnel of the Merchant Marine who were serving on Army-owned or Army-controlled vessels, and to certain “attached civilians” eligible and desiring to vote (Martin 730). The Navy did the same. The War Shipping Administration gave Federal War Ballots to “…eligible seamen on vessels outside the United States having no gun crews and to eligible seamen ashore outside the United States for hospitalization, reassignment, or repatriation (Martin 730).

Regular and air mail postal mailing was free for service members in this election. While members of the Army, Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard were approved to use either the state or federal ballot, approval of other organizations varied. For example, the Merchant Marine was recognized by the federal government, but some states did not recognize the “officer status” of Merchant Marine Officers (Carter 31). This resulted in many Merchant Marine ballots being thrown out in at least nineteen states that did not recognize them (Martin 731). Additionally, the American Field Service personnel (who had 60-70 thousand overseas) were not authorized to use the 1944 election procedure (Carter 32). Members of the Red Cross, Society of Friends, the USO, and the Women’s Auxiliary Service Pilots were authorized by the federal government to use the procedure but were unauthorized to use the procedure in some states.

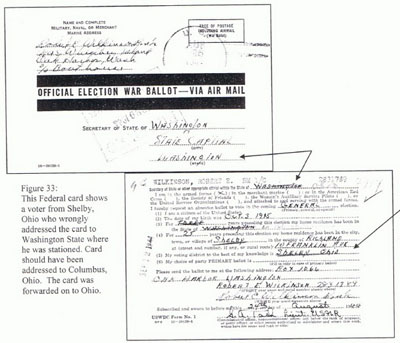

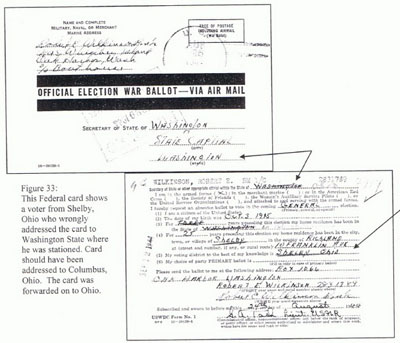

Due to the confusing nature of voting in 1944 some ballots were thrown out due to irregularities. Most irregularities were the result of a soldier sending his/her ballot into the state where they are on duty not residing, submitting a federal war ballot without a federal war ballot return-envelope, and submitting a state ballot without a state ballot return-envelope (Carter 38).

Soldiers serving in the Pacific encountered a unique irregularity. The return-envelope gum would often get stuck down to the envelope. If the flap was damaged in any way it would thrown out as it would have the appearance of being tampered it (Carter 39). Though, officers keen to this problem would write on the envelope, “Envelope flap stuck when received requiring forced opening before voting” and sign their name before mailing it (Carter 39).

Example of confusing nature:

The process of voting was rather mundane for most soldiers. One soldier describes that “on Sept 27th around Villers-les-Moivron, I had mailed an absentee ballot for the coming election. I put an X by the candidate of my choice and sent it back with one the cooks to be mailed. I wonder if the rain at home kept people away from the polls” (Adkins Jr. and Adkins III. pg. 74-75).

Though, voting at the front could be dangerous. In one instance an officer killed taking completed ballots to an APO. In a second, a Japanese bomb was dropped and destroyed, along with other things, all the voting records for a unit. In a third, the Germans attacked and captured ballot supplies and took several Americans as prisoners who were in the process of voting. Unfortunately, for prisoners no voting materials were sent them as it would require them to release military information (Carter 39-42).

The vast majority of overseas personnel used the state ballot. Military voters from KY and NM had to use the Federal War Ballot as their state lacked military absentee voting rules. Out of the 4.9 million eligible overseas military voters, 108,691 used the Federal War Ballot and 4.5 million used the state absentee ballot with 3.2 million state absentee ballots being returned (Anderson 95).

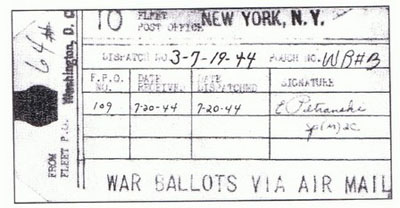

Example of Federal War Ballot Mailbag Tags

1945

Voting for local, state, and primary elections in 1945 used the same procedure in 1944 but without the need for a federal ballot unless it was a special congressional election. By Sept. 1945 a Form 76 was created (it came in both a small and a later revised larger one) which revised and replaced the Form-1 and Form 560. Though, the earlier forms continued to be used in applying for an absentee ballot.

Form 76 larger and smaller

By April 1946 laws did away with the Federal War Ballot for any type of election be it congressional (special or regular) or Presidential (Carter 46).

Sources

Adkins, Andrew Jr. and Andrew Adkins III. 2005. You Can't get Much Closer Than This: Combat with Company H, 317th Infantry Regiment, 80th Division. Casemate, Havertown, PA. Pg. 74-75.

Anderson, Michael. 2001. "Politics Patriotism, and the State: The Fight Over the

Soldier Vote, 1942-1944." In Politics and Progress: American Society and the

State Since 1865. eds. Andrew E. Kersten and Kriste Lindenmeyer. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Carter, Russ. 2005. War Ballots: Military Voting by mail from the Civil War to WWII.

USA: Military Postal History Society.

Martin, Boyd. Aug. 1945. “The Service Vote in the Elections of 1944.” American Political Science Review. Vol. 39. No. 4. pp 720-732.

Yank, March 17th 1944. Vol 2 No 38. pg 14.

Link: http://www.scribd.com/doc/82044516/YANK-Soldier-Responses |